|

The Stations of the Cross are on display at St. Mark's. The Stations of the Cross were painted by the artist Randall M. Good and were donated by Phil Cato in honor of his parents, Mr. and Mrs. Lile Cato.

Station I

Jesus is Condemned to Death In a somber, tent like atmosphere, The Way Of The Cross begins. Pilate holds the fasces, a Roman symbol of judicial authority, as he points to the cross piece and the way that Christ must go. The pose of Jesus is a variation of the Ecce Homo. The design of this figure deliberately envisions Christ’s acceptance of the awful path to come and the magnitude of His sacrifice. The intense red of Pilate’s mantle is an example of the symbolic function that color serves throughout the series; in this case it is the first foreshadowing of the blood to be spilled. |

|

Station II

Jesus Takes Up The Cross In Station II, Christ’s bearing emphasizes the symbolic, rather than the narrative, aspect of the scene. He appears heroic, willingly taking up the cross for the redemption of mankind. All of the elements in the composition contribute to this effect, from the dramatic diagonal of the patibulum, to the swag of drapery in the background. At the lower right I placed a lamb, touching the cross, as a symbol of the approaching sacrifice. Furthermore, it is not unintentional that the blood red sky of early morning seems to touch the breast of the lamb. |

|

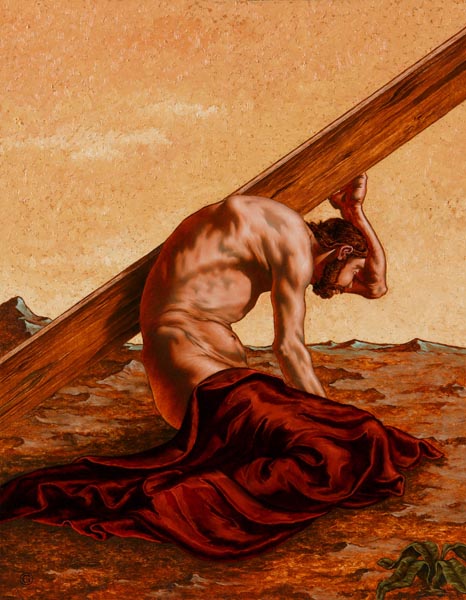

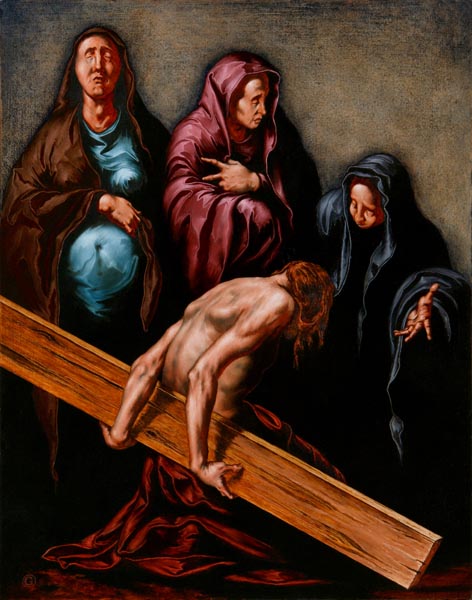

Station III

Jesus Falls For The First Time After the heroic nature of His pose in the preceding panel, I wanted to strike the viewer with the physical torment of Jesus in Station III. He is a knot of struggling bone and skin, muscle and sinew. The yellow background of the morning sun isolates and emphasizes His distress. By manipulating this ebb and flow through color and compositional devices, I sought to portray the full pathos of the passion and bring the viewer into the journey. |

|

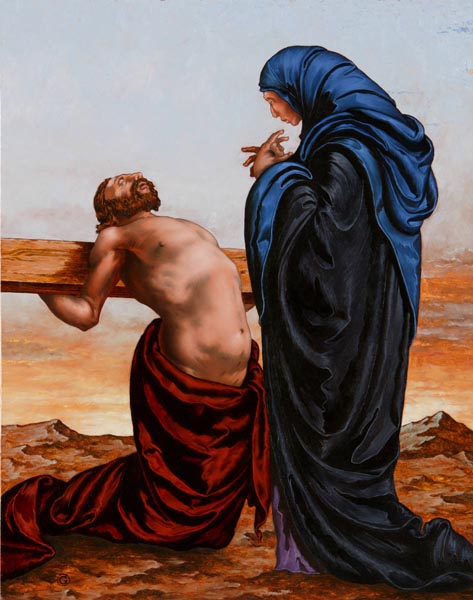

Station IV

Jesus Meets His Mother Christ, under the wooden load, has stumbled in front of Mary. Pictured before a light blue sky with strips of the receding dawn at the bottom, the figures appear monumental, silhouettes of drapery and dramatic intensity. By placing the Madonna at an angle to the picture plane looking in, we the viewers become participants, witnesses who respond empathetically. Christ presents Himself as if He were already nailed to the Cross. This device is a foreshadowing of Station XXI, and in both paintings a world is communicated in the heartrending gaze between Mother and Son. |

|

Station V

Simon Takes the Cross For Jesus Portraying Christ completely collapsed on the ground in Station V, allowed me to create a dramatic diagonal as Simon takes up the patibulum. THe prostration of Jesus is in contrast to Simon’s vigorous action and flowing mantle. The singular compassion of Simon’s act of lifting the cross, contrasts directly with the two unfeeling witnesses in the background. Separated by a small tree that alludes to the Tree of Life, they look anywhere but at the drama, refusing to acknowledge the events around them. This is an example of a symbolic detail that runs through the series. In this case, by turning their backs physically and metaphorically to Christ and the cross, they turn their backs on salvation. |

|

Station VI

The Veil of Veronica There are few stories as touching as that of Veronica. Here veil was imprinted with the face of Jesus when she mercifully wiped away His blood and sweat. This painting is a counterpoint to the preceding panel. Where Station V is dramatic, The Veil of Veronica is quiet and tender. Christ assumes an almost physically impossible attitude in which He maintains contact with the cross, yet seems to lay His head in the hands of Veronica. She gently bends down to receive His brow. He is all tormented and bent flesh; she is a pillar of drapery and softness. |

|

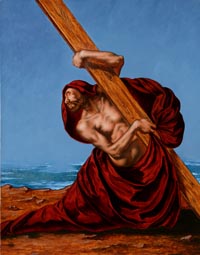

Station VII

Jesus Falls a Second Time Here, in Jesus Falls a Second Time, the heroic bearing of Christ in Station II is revisited. The design of this composition continues the rhythm of Christ’s poses in the series. Here at the halfway point, it provides a respite from the physical agonies of the first scenes, while looking ahead to the drama of the approaching climax. The design also emphatically restates the symbolic function of composition and color. Christ seems to rise out of the earth, His flesh and billowing drapery shining against the chromatically intense blue of the afternoon sky. |

|

Station VIII

Jesus Before the Women of Jerusalem The unique perspective in Station VIII makes the experience more visceral. Seen from behind Christ, the viewer becomes like Him, an afflicted body moving down a dark path. The hands of the women play out the words from the liturgy. As the woman on the right reaches toward Jesus we hear Him say, “Do not weep for me …” The gestures continue the theme as the central woman touches her breast, “… weep for yourselves …” And finally, as the woman on the left cradles her pregnant belly, the words echo and fade in our ears, “… and weep for your children.” |

|

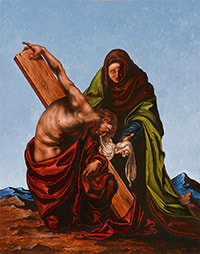

Station IX

Jesus Falls a Third Time Jesus is exhausted; the terrible journey is near its conclusion. Station IX recalls the overwhelming gravitas of Christ’s relationship to the earth. He falls under the weight of the cross and His sacrifice. Under an ominous bruised sky with a blood red horizon, Christ peers at the half buried skull that represents Golgotha. The strained posture of His arms prefigures the Crucifixion. We are transfixed by empathy; we have become witnesses and beneficiaries to an event greater than ourselves. |

|

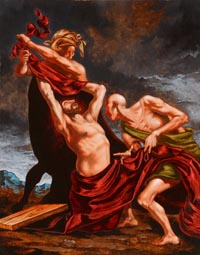

Station X

Jesus is Stripped of His Garments In Station X, two executioners tear away Christ’s robe; one pulls up and into the picture plane, the other down and toward the viewer. This composition heightens the drama and fills the panel with violent movement. Furthermore, the crepuscular and agitated sky contributes to the sense of action. In the figure of Christ, I imagined His aching muscles and bruised flesh still fighting, resistant to yet another indignity inflicted by the very souls He was sent to redeem. |

|

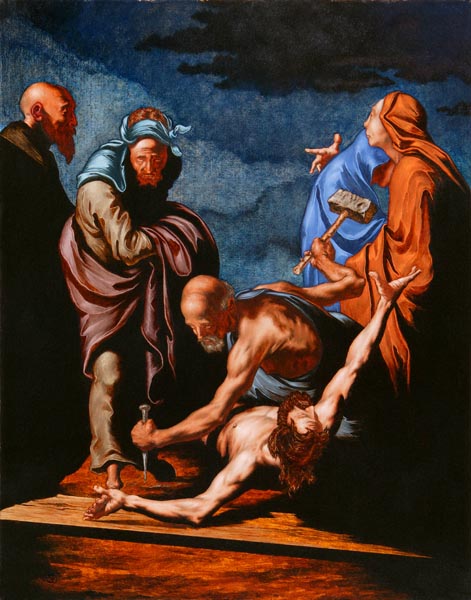

Station XI

Jesus is Nailed to the Cross Like a snapshot in a lightning store, the Crucifixion begins against a wall of darkness and humanity. The hammer is poised to strike, the first nail is about to pierce Christ’s flesh. The V-shaped composition focuses attention on the nail and splits the responses of the figures in the painting. The pathos is tangible as Christ reaches toward Mary and a companion who react in shock, in sadness, and in sympathy. To the left, an observer casually helps the executioner by pressing down Christ’s hand with his foot, while another figure, in an aura of black, seems blissfully unconcerned. |

|

Station XII

Jesus Dies on the Cross For the first time in the series, Christ is a strong vertical element. His mantle, once the color of blood and earth, is now purified by the Crucifixion and shines white against a sanguine sky. Christ is no longer of the earth. He is released; He is transcendent. The full pathos of the sacrificial apotheosis is expressed in Mary’s gaze, uplifted in maternal angst, and in the devoted embrace of Mary Magdalene. |

|

Station XIII

Mary Holds the Body of Jesus Christ’s body, once received by the cruel cross, is received into the loving embrace of His Mother. Her erect yet gentle form defies the claims of earth and bears the impossible burden. Her figure is pure mannerist invention. Mary’s attenuated neck and back arch protectively over Christ. As she did when He was an infant, she holds her son to her breast, wrapped in the soft folds of her garments. The penumbra of white cloth that surrounds the tender tableau also touches the remnant of the patibulum, which recedes into the background. All of the pathos that has been building in the long journey is released in this final embrace of mother and child. |

|

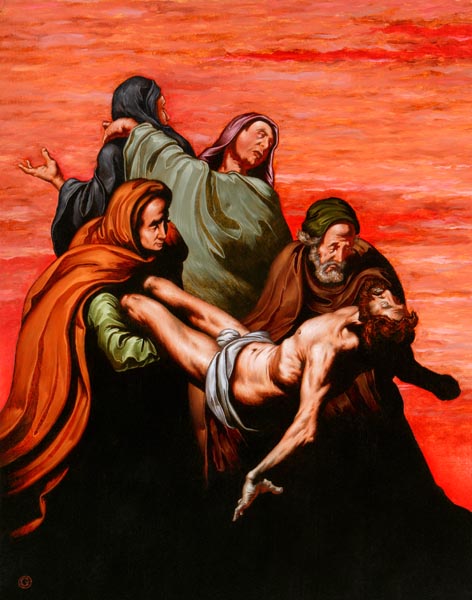

Station XIV

Jesus is Place in the Tomb The cross, barely visible in the previous panel, is now absent. Christ, suspended above the earth on final time by a group of mourners, is lowered toward the unseen tomb. The introduction of green, pink, and golden orange to the palette points to Spring and the Resurrection. The sacrificial apotheosis is complete, as Christ’s body is held out toward the viewer. Not only is it an invitation to participate in the drama, but The Savior is presented as a gift to all who would walk the way of the cross. |

|

About the Artist

Randall M. Good Randall M. Good received a Bachelors of Fine Arts degree from the University of North Texas in 1991. His studies focused on studio painting and art history, in particular the Italian Renaissance and Mannerist period. After graduation, Randall’s work as a conservator at Art Restorations Inc. in Dallas further developed the young artist’s technical knowledge. In subjects ranging from Catholic iconography to Greek and Roman mythology Good’s intent is unwavering – to utilize aesthetics to engage the viewer emotionally and intellectually. One collector, Father Aaron Pirrera, of Subiaco Abbey, says this about Good’s artwork: “The old, perhaps “tired” themes, take on a new meaning with Randall’s interpretation. But yet, like the old masters, the works evoke a sense of the mysterious and the divine…a rare combination of pathos and beauty…and for me an excitement to go back and study the stories of the saints again.” In the 2007 show, In The Company Of Angels, Good began to explore a personal creation myth inspired by a host of sources – literary to cosmological, religious to mythic. In his hands, the tradition of Florentine disegno becomes a vehicle for remarkably modern expression. Good has shown at Blue Moon Gallery, owned by Patricia Scavo and her daughter, Dishongh Scavo, since 1999. In 2002, through an exclusive agreement, the gallery became the premier source for works by Randall M. Good. Patricia says, “What I admire most about his artwork is how deftly he mixes Renaissance aesthetics with modern elements, yet still pays homage to his predecessors in his contemporary compositions.” A Texas native, Good has lived in California and Ireland. He now resides in Denton, Texas, with his wife Anadara Braun-Good, an interior designer, and their two Weimaraners – Harley and Lacey. Artist's Statement

The Way of the Cross The Passion of the Christ in Art The artists who inspire me, Michelangelo, Pontormo, and Fiorentino, saw public commissions as a chance to display their talents and push themselves to the limits of their abilities. Almost 500 years later I perceived the commission for the Stations of the Cross in the same way, as both an opportunity and a challenge. I embraced this chance to make an age-old staple of church decoration modern and vital, by treating each painting in the series as its own individual, self-contained work of art. I employed the principles of Florentine disegno to create brilliantly colored and expressively composed pictures that would compliment, yet remain affective within their ultimate home, a 100 year old church solemnly lit by stained glass windows. To meet the challenges of the subject, I chose to emphasize two elements that should be examined prior to considering the images and the accompanying notes. First, portraying Christ with the single cross piece, or patibulum, allowed me to manipulate the figure in a mannerist fashion to create expressive attitudes and avoid the poses of older treatments. Secondly, both color and composition function in a symbolic manner. The vibrant colors of the background suggest the passing day and heighten the emotional impact of each scene. Christ’s humanity is emphasize throughout the first eleven paintings. His cloth, so different from the traditional blue and white, is the color of blood tainted earth. The rhythm of the poses and His bent and weighty bearing, magnify His proximity to the earth. The final three panels are an expression of His sacrificial apotheosis. His drapery, now white, signifies purity as He is lifted above the earth in a visual representation of the awesome power of sacrifice, love, and mercy. Using the elements of disegno – drawing, composition, and color, enables me to create works of art imbued with great pathos. It is my hope that the paints of THE WAY OF THE CROSS will do what the Stations of the Cross have done for centuries – tell a story and in so doing touch the hearts and minds of the viewers. — Randall M. Good |